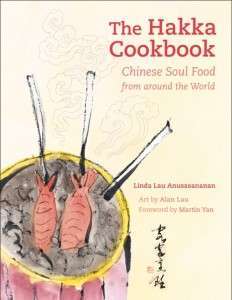

One of the Hakka classics, stuffed tofu (nyiong tiu fu in Hakka), was a creation of migration. When the Hakka came to Southern China, they wanted to make the dumplings they had eaten in the north. However, they couldn’t find the wheat flour needed to make the dumpling wrappers. So they improvised and placed the filling into what was available—chunks of tofu (aka bean curd). The stuffed tofu was cooked many different ways: browned and braised, deep-fried, steamed, or poached.

The original filling was pork because that was what was available to these inland-bound people. When they migrated to the coast, seafood was sometimes mixed with the pork. Hakka versions of stuffed tofu almost always contain some pork that deepens the flavor. This pork addition distinguishes it from Cantonese versions which commonly use a light fish mousse-like paste as a filling. One Hakka from Singapore told me that by comparing the Cantonese and Hakka versions of stuffed tofu, you can see the differences between the two cuisines. The Hakka like stronger, more robust flavors and heartier dishes. The Cantonese profile is lighter with more subtle, delicate flavors.

The highly versatile savory filling for stuffed tofu appears in many guises. Cooks fill chiles, bitter melon rings, mushrooms, and eggplant with pork mixture. It is even used to fill wonton. There are endless variations.

In The Hakka Cookbook look for Braised Pork-Stuffed Mushrooms (page 61), Stuffed Bitter Melon in Tomato Sauce (page 163), Stuffed Bitter Melon Soup (page 24), Braised Fried Tofu with Pork (page 76), Singapore Stuffed Vegetable and Tofu Soup (page 106), Uncle Henry’s Stuffed Tofu Triangles, and Natalie Com Liu’s Tofu Topped with Pork.

One of my favorite fillings comes from my friend Fah Liong, who migrated from Indonesia to California. In Fah’s Stuffed Tofu Triangles (page 215), she mixes pork with chopped shrimp, shiitake mushrooms, green onions, and fish sauce. She stuffs the filling into slit-like pockets cut into triangles of tofu and steams or poaches the triangles in broth.

One of my favorite fillings comes from my friend Fah Liong, who migrated from Indonesia to California. In Fah’s Stuffed Tofu Triangles (page 215), she mixes pork with chopped shrimp, shiitake mushrooms, green onions, and fish sauce. She stuffs the filling into slit-like pockets cut into triangles of tofu and steams or poaches the triangles in broth.

You could also mound the filling onto tofu squares or fill vegetable cavities. Vary the seasonings and proportion of pork and shrimp to suit your tastes.

Fah’s Pork and Shrimp Filling

Makes about 1 cup, enough to fill about 1 pound tofu

2 dried shiitake mushrooms, each about 1 1/2 inches wide

4 ounces peeled, deveined shrimp

4 ounces ground pork

2 tablespoons thinly sliced green onion, including green tops

1 tablespoon Asian fish sauce

2 teaspoons cornstarch

1/4 teaspoon salt

1/8 teaspoon white pepper

1. Rinse the dried mushrooms and place in a small bowl. Cover with hot water and soak until soft, 20 minutes to 2 hours, depending on thickness. Squeeze out excess liquid. Remove and discard mushroom stems and finely chop the caps.

2. Finely chop the shrimp. In a bowl, mix the mushrooms, shrimp, pork, green onion, fish sauce, cornstarch, salt. and white pepper. Use to fill tofu and vegetables. Pan brown and braise, steam, poach, or deep-fry as recipe suggests.