Need a quick, no-fuss, healthy dinner? Steamed fish, rice, and green vegetables is my go-to meal that cooks in one versatile pan—a Chinese multi-layer steamer. With relatively little effort, I am rewarded with a complete meal highlighted by moist succulent fish.

Need a quick, no-fuss, healthy dinner? Steamed fish, rice, and green vegetables is my go-to meal that cooks in one versatile pan—a Chinese multi-layer steamer. With relatively little effort, I am rewarded with a complete meal highlighted by moist succulent fish.

The origin is Chinese. In a Hakka restaurant in Meizhou, China, we ate a steamed whole fish, very simply seasoned with a bit of ginger, rice wine, soy sauce, and green onions (page 39 in The Hakka Cookbook). Throughout China, we ate different variations of steamed fish, sometimes with fermented black beans, chiles, red peppers, and pickled mustard greens. In Meizhou, we also ate rice steamed in small clay bowls (page 270 in The Hakka Cookbook). I merge these two in this easy, quick meal.

With a big Chinese steamer this meal cooks efficiently in about 30 minutes. I use a self-contained multi-layer metal steamer. You could also use two stacked bamboo steamer racks over a 14-inch wok. Cook bowls of rice on one layer and fish on the top layer. When both are done, plunge vegetables into the boiling water in the base pan and cook briefly, then drain. Look for the steamers at the Wok Shop, Asian cookware stores and Asian supermarkets, and online. Choose steamers or bamboo steamer racks at least 11- to 12-inches wide to accommodate wide plates.

Steamed Fish and Rice for 2

In this easy version, I often use a piece of fish fillet. You can also use a small whole fish and increase the seasonings. Season fish as you like: choose from shiitake mushrooms slivers, sliced chiles, dried hot chile flakes, pickled mustard green slivers, lemon slices, fresh herbs. If desired, lightly mix the cooked green vegetables with Chinese oyster sauce and sesame oil to taste.

2/3 cup white long grain rice

12 to 16 ounces fish fillet such as rock fish, salmon, or halibut

1 tablespoon Chinese rice wine (shaoxing)

1 tablespoon soy sauce

1 tablespoon thinly slivered fresh ginger

1 tablespoon fermented black beans, rinsed (optional)

Salt to taste

1 green onion, thinly sliced or slivered, included tops

6 to 8 ounces Chinese green vegetable such as Chinese broccoli (gai lan) or yau choy (ends, trimmed and cut in 3-inch lengths), or baby bok choy (cut in halves or quarters lengthwise)

1 tablespoon vegetable oil or sesame oil

Cilantro leaves (optional)

1. Fill the base of a Chinese metal steamer half to two-thirds full of water or a 14-inch wok (if using bamboo steamer racks). Set wok over a ring if it has a round bottom to stablize. Bring water to a boil over high heat.

2. Rinse 1/3 cup rice in fine wire strainer; drain. Place rice in a small Chinese rice bowl (about 1 cup size). Fill bowl with 1/3 cup water. Repeat for second bowl. Repeat if you want additional bowls of rice. Place rice bowls in one steamer rack. When water boils, set filled steamer rack over water, cover and steam about 15 minutes.

3. Meanwhile rinse fish and pat dry. Place fish (skin-side down, if attached) on shallow heatproof dish (such as a 9-inch Pyrex pie pan) that will fit inside a steamer. Drizzle fish evenly with wine and soy sauce. Sprinkle evenly with ginger, black beans, and salt. Sprinkle white part of onion over fish. Set fish in second steamer rack.

4. After rice has steamed 15 minutes, set steamer rack with fish on top of rack with rice. Cover fish. (In a wok, you may need to add more boiling water as it evaporates.) Continue steaming until fish looks almost opaque in thickest part, 8 to 10 minutes for about 1 inch thick piece and rice is tender. In a wok, you may need to add more boiling water as it evaporates. When fish is done, lift off both steamer racks and set the stacked racks on a towel-covered counter. (Be careful, steam is very hot.) Keep steamer racks covered and allow fish to rest.

5. Add more water to pan if pan is less than half full and return to boil over high heat. Add vegetable and cook until bright green and barely tender, about 2 minutes. Drain, place vegetable in a serving bowl.

6. Sprinkle remaining green onions over fish. In a small pan over high heat, cook the vegetable oil until very hot and pour over green onions and fish. If using sesame oil, do not heat. Sprinkle fish with cilantro. Serve fish with rice and vegetables.

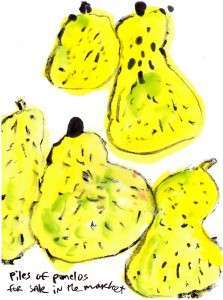

An exciting new kind of Chinese cookbook is at the press. About 6 months ago, The Cleaver Quarterly, a magazine devoted to Chinese food and its diversity, invited me to contribute a recipe to their new project, The Illustrated Wok. Forty chefs paired with forty artists would produce a picture cookbook, illustrated with hand drawn art. Each recipe would be brought to life with colorful unique illustrations.

An exciting new kind of Chinese cookbook is at the press. About 6 months ago, The Cleaver Quarterly, a magazine devoted to Chinese food and its diversity, invited me to contribute a recipe to their new project, The Illustrated Wok. Forty chefs paired with forty artists would produce a picture cookbook, illustrated with hand drawn art. Each recipe would be brought to life with colorful unique illustrations.