Khiung Hee Fat Choy! (Hakka dialect) May you have a prosperous New Year! Chinese New Year arrives January 31 and families will gather for a special meal over the next two weeks.

Khiung Hee Fat Choy! (Hakka dialect) May you have a prosperous New Year! Chinese New Year arrives January 31 and families will gather for a special meal over the next two weeks.

Many will eat traditional meals filled with foods that sound like fortuitous words or whose shape or color symbolizes prosperity, unity, wealth, fertility, family harmony, or good fortune. Oranges, mandarins, and kumquats resemble gold. Lettuce signifies prosperity. Whole fish symbolizes prosperity. Spring rolls, with their shape of a gold bar, represents wealth. Shiitake mushrooms, a symbol of longevity, also relate to seizing opportunities. Whole chickens with head, tail, and feet indicate completeness. Green vegetables represent close family ties. You will find many recipes that use symbolic ingredients throughout The Hakka Cookbook. However, if you want to try something new, consider these special dishes I discovered in my travels for the cookbook.

Basin Feast (puhn choi, page 82)

We gasped when the waitress set a huge metal basin filled with a mountain of food before us. We were at Chung Shing Restaurant in In Tai Po, New Territories of Hong Kong, The pan was literally a wash basin layered with a multicourse feast. This one-pan feast is popular for family gatherings such as Chinese New Years and weddings because everyone eats from one dish which symbolizes unity. Guests gather around the basin and literally eat from top to down, working their way through the courses.

Vegetable Tea (choi cha, page 113)

During the first ten days of Chinese New Year Loy Sye Moi makes Vegetable Tea (page 113) which is basically an artfully presented healthy vegetable soup. She arranges eight different stir-fried greens in each bowl to create a pretty kaleidoscope of greens. Eight is a lucky number and represents good fortune. Each vegetable contributes a different flavor and texture. She pours a clear broth carefully over the vegetables and garnishes with spoonful of ground peanuts and sesame seeds.

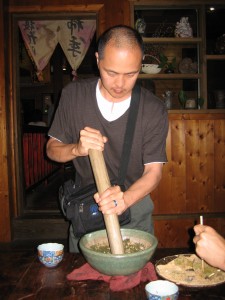

Savory Pounded Tea Rice (lui cha fan, page 119)

A heartier variation of vegetable tea is made by the Ho Po clan, a Hakka subgroup who serve it for Chinese New Year. This version includes rice and a pounded herbaceous tea. I first tasted this healthy rice bowl in Singapore and later Amy Wong from Malaysia shared her recipe with me. A bevy of vegetables, tofu, and peanuts blanket a bowl of garlic rice. Pour a tea, made from pounding fresh green herbs, dry tea leaves, nuts, and seeds, over the rice and mix together for deliciously wholesome rice bowl. It’s a healthy and energizing way to start the new year.

Taro Abacus Beads (wu tiuh pan jue, page 125)

In Singapore I encounter Taro Abacus Beads. Their name comes from their shape which resembles the pierced disks on a Chinese abacus, an ancient, low-tech adding machine. Hakkas often cook this dish for Chinese New Years to bring wealth in business. These chewy pasta disks resemble a springy, sticky version of Italian gnocchi. Taro replaces potato and tapioca starch replaces wheat flour typically used in Italian gnocchi. The Hakka version has a nuttier flavor and chewy texture. Stir-fry the boiled taro abacus beads with vegetables or cloak with a mushroom pork sauce.

Whatever you cook, Khiung Hee Fat Choy! May you have a delicious, prosperous, and happy new year!