Popo (grandmother) loved to garden. One of my favorite vegetables was her Chinese long beans that measured almost two feet long.

Popo (grandmother) loved to garden. One of my favorite vegetables was her Chinese long beans that measured almost two feet long.

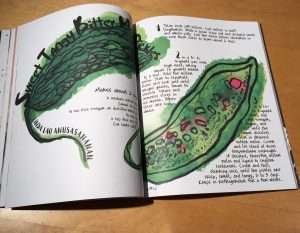

Last weekend at the farmers’ market long beans (aka yard long beans) were back in season. This variety is related to black-eyed peas or cowpeas so they have a heartier bean flavor than common crunchier green beans. I bought a bundle of the slender dark green beans (they can also be light green) and cooked them as Popo (grandmother) would in this easy stir-fry with pork and a dark savory bean sauce.

Look for the ground bean sauce in Asian markets. Other names for it are bean sauce, brown bean sauce, yellow bean sauce, bean paste, mo chi jiang, meen see, mo see chiang) This thick, pasty sauce is made from ground fermented soybeans. It has a salty, pronounced fermented bean flavor, akin to soy sauce. For an alternative, you could use hoisin sauce which is a sweetened spiced version of bean sauce. Eliminate the sugar in the sauce, if used.

Stir-fried Long Beans and Pork (page 21 of The Hakka Cookbook)

Makes 2 servings as a main dish or 4 servings as part of a multicourse meal

Sauce:

1/4 cup water

1 tablespoon Chinese rice wine (shaoxing) or dry sherry

1 tablespoon soy sauce

1/2 teaspoon sugar

1/2 teaspoon cornstarch

Stir-fry:

8 ounces long beans

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

1/2 cup chopped onion

1 tablespoon minced garlic

4 to 8 ounces ground pork

1 tablespoon ground bean sauce

1/2 cup water, or as needed

1. For the sauce: In a small bowl, mix the water, wine, soy sauce, sugar, and cornstarch.

2. For the stir-fry: Trim off the stem ends from the beans and cut the beans into 1/2-inch lengths.

3. Set a 14-inch wok or 12-inch frying pan over high heat. When the pan is hot, add the oil and rotate pan to spread. Add the onion and garlic; stir-fry until the onion is lightly browned, about 1 minute. Add the pork and stir-fry until the meat is browned, 1 to 2 minutes. Stir in the bean sauce to coat the pork. Add the water and beans. Cover and cook until beans are barely tender to the bite, 1 to 2 minutes. Stir the sauce mixture and add to the pan. Stir-fry until the sauce boils and thickens, about 30 seconds. With a frying pan, the sauce may be thicker. If needed, stir in 1 to 2 tablespoons water to thin sauce. Transfer to a serving dish.