Chuxi Tulou Cluster

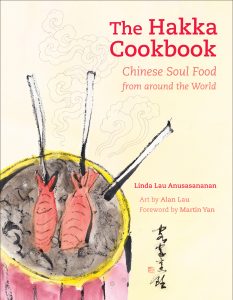

Last week, I visited some of the earthen structures built by our Hakka ancestors known as tulou (??) located in Yongding County in Fujian Province in China. The large tall structures with thick load-bearing rammed earth walls were designed to keep out bandits and house a group of families. Many are designated UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Chuxi Tulou Cluster

During the Cold War, it is said when viewed from space their unusual shapes and sizes looked like missile sites or nuclear reactors. On the ground, inspectors found that they were simply large homes for a group of Chinese families.

Many were designed with a distinctive round shape. Built in a circular shape to thwart bandits, these multi-story homes were virtually earthen fortresses. Their round shape made it easier to defend with no corners for enemies to hide behind. The tall height gave them a better vantage point to attack their enemies. Thick walls kept bullets and attackers out.

Families lived together, each usually occupied a vertical section of the round, sort of like a pie-shaped wedge. In most of the tulou we visited, the bottom floor was the communal area with kitchen and ancestral hall. Upper floors were for sleeping and storage.

Zhenchenglou at Hongkeng Tulou Cluster

We spent the afternoon and night at Hongkeng Tulou Cluster to experience the life in a Hakka village without the crowds. Early in the morning, we visited the double-ring Zhenchenglou tulou built in 1912 built by a tobacco knife trader.

We slept at the138-year old Tulou Fuyulou Changdi Inn. At this square-shaped tulou, we ate Hakka meals in the courtyard, tasted the family’s local teas–oolong, orange, and flower–and slept upstairs in the bedrooms retrofitted with Western toilets. As we toured the village, we saw families cooking dinner, tending their vegetable gardens, children playing, and mustard greens drying in the courtyards. It’s a quiet life. These days mostly seniors and children occupy the village. Most of the young people have gone to the big cities to work and make money.

We slept at the138-year old Tulou Fuyulou Changdi Inn. At this square-shaped tulou, we ate Hakka meals in the courtyard, tasted the family’s local teas–oolong, orange, and flower–and slept upstairs in the bedrooms retrofitted with Western toilets. As we toured the village, we saw families cooking dinner, tending their vegetable gardens, children playing, and mustard greens drying in the courtyards. It’s a quiet life. These days mostly seniors and children occupy the village. Most of the young people have gone to the big cities to work and make money.

The Chuxi Tulou Cluster, inhabited in the 14th century by the Xu clan dates back to the Ming dynasty. This picturesque Hakka village contains primarily round and rectangular shaped tulou. Unfortunately the oldest and largest one, Jiquing Lou, was closed for renovation when we there.

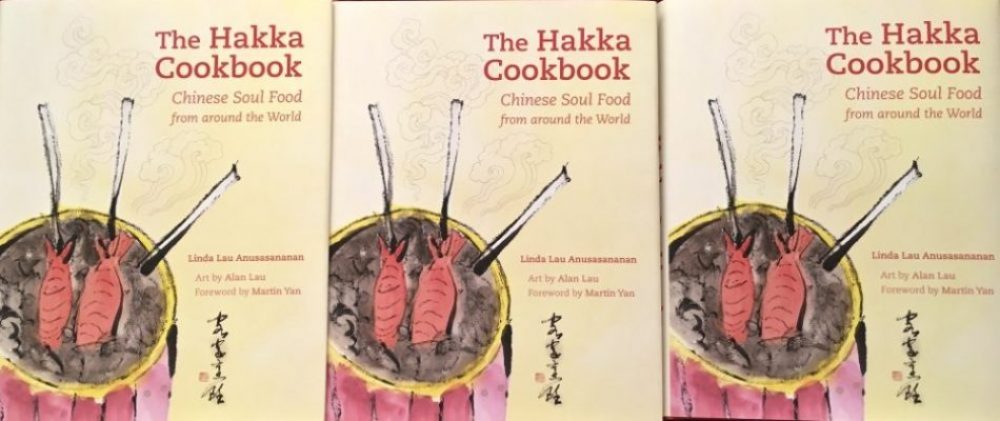

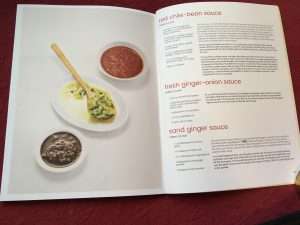

Join me for at the Menlo Park Library Monday, August 13 at 6:30 pm for a slide show and cooking demo on Hakka Soul Food. Learn about the Hakka Chinese and how their unique history of migration influenced their food. Afterwards, I will demo 3 or 4 recipes. Tasting will follow. The event is free. Hope to see you there!

Join me for at the Menlo Park Library Monday, August 13 at 6:30 pm for a slide show and cooking demo on Hakka Soul Food. Learn about the Hakka Chinese and how their unique history of migration influenced their food. Afterwards, I will demo 3 or 4 recipes. Tasting will follow. The event is free. Hope to see you there!