Last month I saw a friend in the farmers market who had just bought some loofah squash. She told me how much she loved it. Her enthusiasm prompted me to buy some. Loofah squash (aka angled loofah, silk squash, Chinese okra) is long and slender with a rough dull green skin. Protruding ridges run down the length of the squash. Inside, the flesh is white and soft which turns silky, slightly sweet, and delicately refreshing when cooked.

Last month I saw a friend in the farmers market who had just bought some loofah squash. She told me how much she loved it. Her enthusiasm prompted me to buy some. Loofah squash (aka angled loofah, silk squash, Chinese okra) is long and slender with a rough dull green skin. Protruding ridges run down the length of the squash. Inside, the flesh is white and soft which turns silky, slightly sweet, and delicately refreshing when cooked.

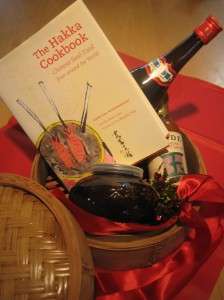

Until I wrote The Hakka Cookbook, I rarely cooked this Chinese summer squash. When my friend Fah introduced me to her recipe Loofah Squash in Egg Flower Sauce (page 216), I discovered its sweet silky nature when gently braised. In Hong Kong, I ate Steamed Loofah Squash with Toasted Garlic Crowns (page 81). Click here to see a food video on this recipe.

Lately, I have discovered it’s firmer nature when stir-fried. I do not add a lot of liquid so the squash does not soften as much. I find this vegetable tastes light, clean, and refreshing, just right for hot summer days.

Stir-fried Loofah Squash and Chicken

Stir-fried Loofah Squash and Chicken

If desired, omit the Chinese sausage and step 2. In step 4, increase the oil to 2 tablespoons.

Makes 2 servings as a main-dish or 4 to 6 servings as part of a multi-course meal

1 boned and skinned chicken breast half (8 oz.), sliced into thin strips

2 teaspoons soy sauce

1 teaspoon cornstarch

1 teaspoon plus 2 tablespoons vegetable oil

1 pound angled loofah squash (about 2 large squashes)

1 Chinese sausage (lop chong), thinly sliced

1 tablespoon thinly slivered fresh ginger

1/2 teaspoon salt, or to taste

3 tablespoons Chinese rice wine (shaoxing) or dry sherry

2 tablespoons chopped cilantro

1. Mix the chicken with the soy sauce, cornstarch, and 1 teaspoon oil.

2. Trim ends off squash. Peel off ridges and skin if tough (if skin is tender, you can leave some on for firmer texture.) Cut squashes diagonally into 1/4-inch thick slices.

3. Set a 14-inch wok over medium-low heat. Add Chinese sausage and cook, stirring occasionally, until sausage is browned, 4 to 5 minutes. Lift out sausage and place in serving dish, leaving the fat behind in pan.

4. Return the pan to high heat. When the pan is hot, add 1 tablespoon oil and rotate pan to spread oil. Add chicken and stir-fry until lightly browned, 2 to 3 minutes. Lift out the chicken and add to sausage.

5. Return the pan to high heat. Add 1 tablespoon oil to pan. Add ginger, squash, and salt. Stir-fry to coat squash with oil. Add the wine and stir-fry until squash is barely tender-crisp, 2 to 3 minutes. (If squash is not tender and begins to burn, add 1 to 2 tablespoons more water and continue stir-frying). Stir in sausage and chicken, Sprinkle with cilantro and scoop into serving dish.