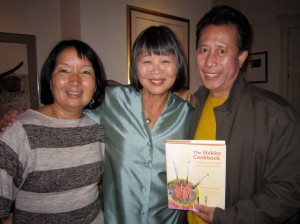

Linda, Nancy, and Ruby proudly display the dishes they cooked.

Gong Hee Fat Choy! Happy New Year! Chinese New Year is almost here. It arrives this Sunday, February 10. In the next couple of weeks family and friends will gather to share food and good wishes. In The Hakka Cookbook, you will find many recipes for specialties served for the New Year celebration. Look under the Hakka Classics for recipes such as Salt-Baked Chicken or Steamed Pork Belly and Preserved Mustard Greens. But if you’re short of time or inexperienced in Chinese cooking, there are many other easy dishes you can cook for a festive meal. For me, the most important part of the celebration is getting together and reaffirming family unity and friendship.

Here are two suggestions for easy Chinese parties that anyone can manage. In the February 2013 issue of Sunset Magazine, look for Build your own bowl by Amy Machnak, pages 84 to 87. The easy noodle buffet party is based on recipes adapted from The Hakka Cookbook.

The second option is a cooking party. It started when a friend suggested we get together and cook from The Hakka Cookbook. Last weekend, eleven of us gathered at Karen and John’s home in Paradise, California, where we cooked and ate a multicourse meal from the book. I designed the menu using seven easy recipes from the book. I proposed instead of trying to cook all the dishes at one time, that we would cook and eat the dishes in several courses, as they were ready. Less stressful for the cooks. People could claim one recipe to make or we could take turns cooking. Karen volunteered to shop and prep most of the ingredients. I would bring ingredients she could not locate and a couple of woks for stir-frying.

You could easily duplicate this plan for your own party. This menu works well for six to eight people. We increased the amounts for a few dishes for our larger group, or you could add more dishes. We cooked rice in a rice cooker, which kept the grain hot throughout our leisurely meal. There was plenty beer, wine, and tea to sip throughout the afternoon. The meal ended with tangerines, cookies, Chinese sesame candy, and candied coconut.

We gathered around noon. It soon became evident, only the women were interested in the cooking as the guys settled outside with beers. Didn’t matter, we gals had a great time reminiscing about old times (we’re known each other since kindergarten) as we cooked our way through the menu.

The Hakka Cooking Party

Melanee serves steeped chicken to wrap in lettuce leaves.

First course: Steeped Chicken (p. 22) with Fresh Green Onion-Ginger Sauce (p. 66). Or use this adapted recipe at specialfork.com Melanee claimed this dish. The chicken and sauce could be up to a day made ahead and brought to the party, ready to eat on demand. She served the moist shredded chicken with lettuce leaves, as a pick-up appetizer.

Second courses: Cumin Beef (p. 183) We had extra beef so we doubled the recipe. However, because it is important not to overload the wok when stir-frying thin meat slices, I cooked the beef in three batches (6 to 8 oz. each) so the slices would brown, rather than stew in its juices. After the initial stir-frying, I returned all the cooked beef to the pan with all the seasonings for a final blending of ingredients.

Stir-fried Snow Peas and Tofu (p. 48). This mild flavored vegetarian stir-fry offers a contrast to the spicy cumin beef. It’s a study of contrasting textures with crisp peas, spongy tofu, and crunchy black fungus.

Third course: Cauliflower and Beef in Black Bean Sauce (p. 27) Phyllis took a turn at the wok and stir-fried this easy meat and vegetable dish. Ruby said she was surprised she liked it because she usually doesn’t like cauliflower. The black bean sauce really adds flavor to this rather bland vegetable.

Karen cuts cauliflower for stir-fry.

Fourth courses: Braised Pork Spareribs in Bean Sauce (p. 203). Since the ribs took longer to cook than most of the other dishes, I cooked them the night before and brought them ready to reheat. I increased the recipe by half since it was just as easy to make more. The savory sauce was delicious over rice.

Chinese Broccoli and Sweet Rice Wine (p. 230). This simple vegetable dish takes only minutes to cook. Ruby learned to cut the vegetables so all pieces are the same size.

Shrimp with Fried Garlic and Chiles (p. 78). Nancy fried bits of garlic and spicy chiles to top stir-fried shrimp.

We ate from noon to five, cooking, eating, and drinking. I directed the cooking and gave hands-on lessons on stir-frying, woks, and ingredients. We found when there’s a lot of cooks, it’s best to have all ingredients prepped ahead of time. Then cooking moves quickly without too much concentration. Everyone agreed they learned a lot, ate well, and would do it again.

To design your own cooking party, follow this easy plan. Have each person or couple be responsible for one dish. The dish could be completely made ahead ( if it works for that dish), or prepped for cooking on site. You can use this menu or design your own based on your own tastes. People take turns cooking and serving their dish. It is sort of like a cooperative home-style Chinese banquet. Enjoy and have fun! Gong hee fat choy!

Kong Hing Restaurant

Kong Hing Restaurant