For most of my life, I never understood what was so special about the Hakka. Popo (my grandmother) insisted, “You should be proud to be Hakka.” Research for my book showed me the answer–the Hakka history. As I learned about their long unique history of migration and how they coped with it, I began to understand how it shaped Popo’s independent, tenacious, hardworking spirit. And how these qualities taught her and other Hakka how to survive where others failed.

Our Hakka History

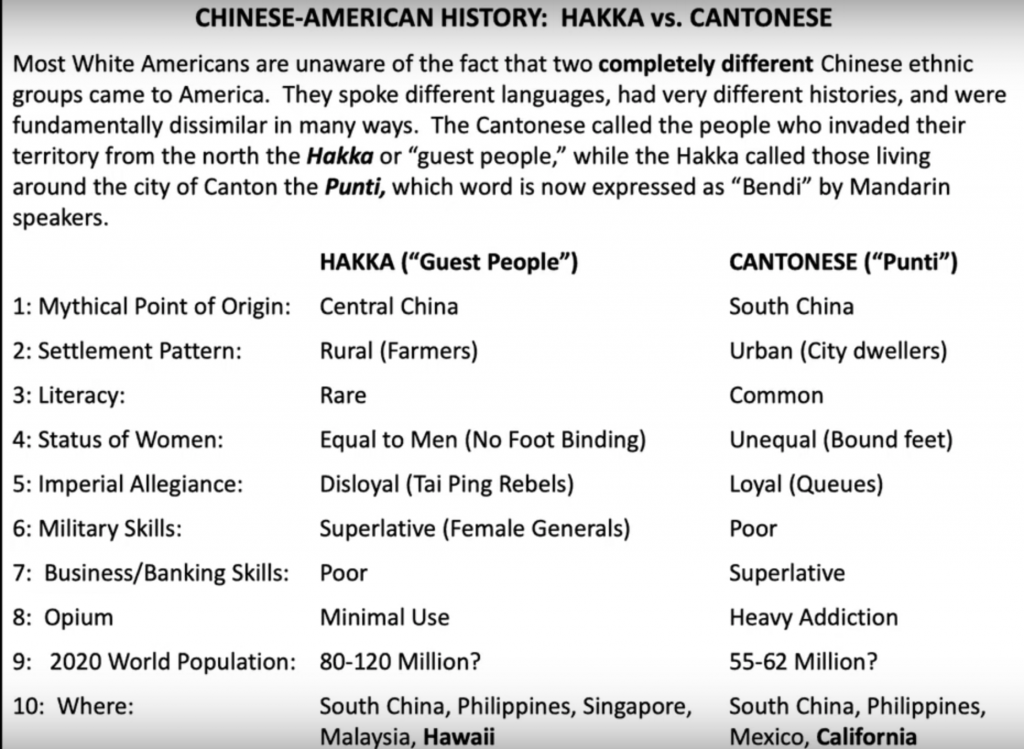

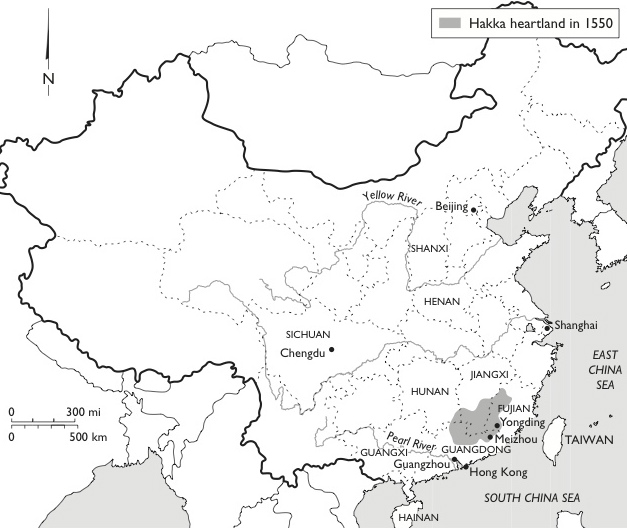

The ancestors of the Hakka originally lived in Henan, along the Yellow River, in north central China. This area was once considered the cradle of the Han, or Chinese culture. Around the 4th century B.C., invaders forced them out of their home. In a series of five mass migrations, war, flood, famine, and drought, sent the Hakka to the south and other remote regions.

The Hakka found shelter in Jiangxi, southern Fujian, and neighboring Guangdong Province. They lived there in relative isolation for almost 400 years (907 to 1279). During this period of relative seclusion they solidified their language, culture, and identity.

Dangerous bandits in Fujian forced them to move across the border to northern and eastern Guangdong Province. The local Cantonese had settled the fertile parcels of lowland. Only scraps of poor hillside land were left for the new migrants. They worked hard and were able to survive where others had failed. Locals labeled the unwelcome newcomers “Hakka” meaning “guest family.” By the sixteenth century, the Hakka began to call the area centered near Meixian in Guangdong and the Jiaying Prefecture (now Meizhou City) as their homeland.

The Hakka spread throughout Guangdong, central and eastern Sichuan, eastern Guangxi, and Taiwan. Through their hard work, they prospered and some become landlords. The local Punti (mostly Cantonese) resented their success. Fighting broke out resulting in the West River Wars and the Taiping Rebellion. This turmoil sent the Hakka all over the world. Now, their estimated worldwide population is over 75 million.

The Hakka Spirit

The history of the Hakka shaped their character and spirit. Chinese society long treated these homeless migrants with contempt. As a result, the Hakka became experts at pulling up stakes, moving on, and starting over. They established settlements in areas where others failed. Eventually they earned respect for their pioneering successes.

It wasn’t until 1933, that the status of the Hakka changed. For centuries, society persecuted the landless migrants. In 1933, Luo Xianglin’s genealogical work showed the Hakka are descendants of the Han dynasty (206 B.C. to 22 A. D.) the Chinese ethnic majority, the Han. This elevated the Hakka to the same status as those who treated them as lower class.

With a shared history of hardship, Hakka proudly see themselves as strong and independent. History tells them work and persistence will bring success.