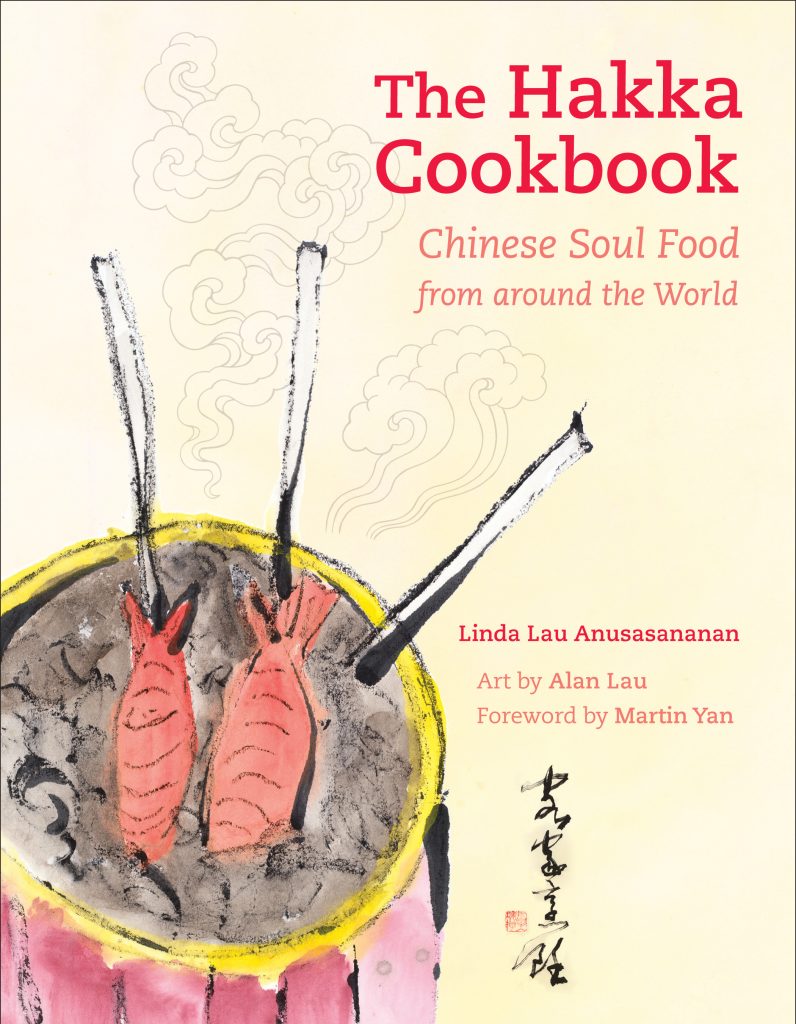

Looking for the perfect gift for your Hakka family or friend? Consider The Hakka Cookbook. It’s a great primer for those who want to know more about their Hakka history and identity.

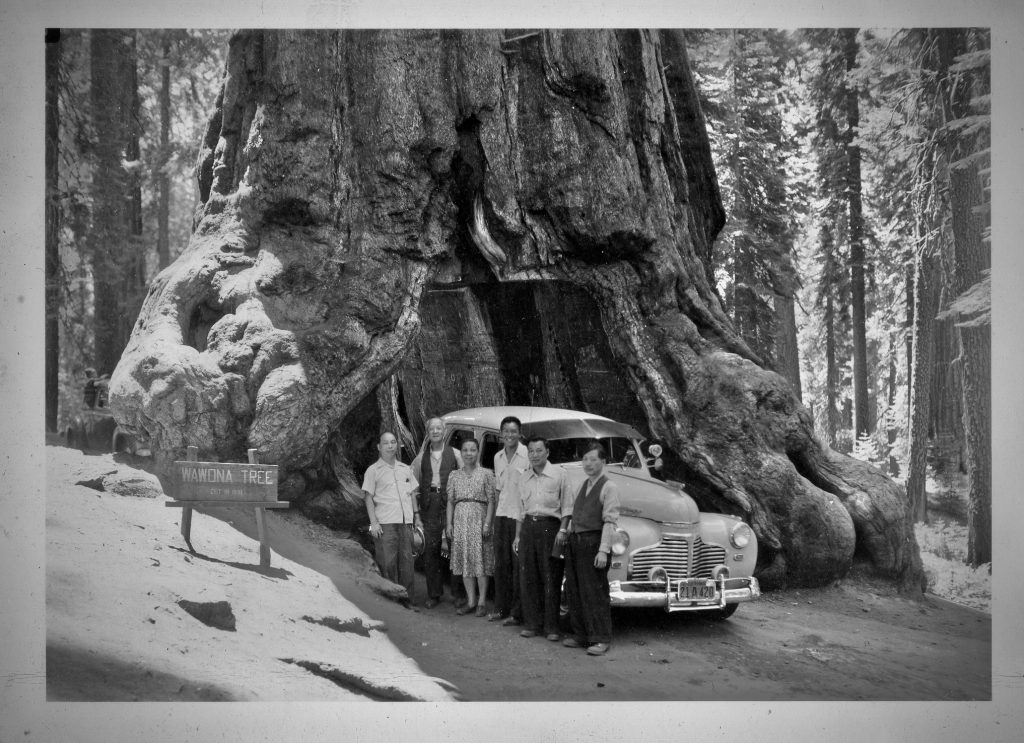

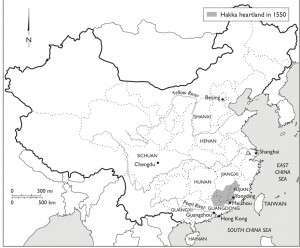

Popo, my grandmother, always told me, “You should be proud to be Hakka.” I never understood why. Long after she passed away, I wrote the book to find the answer. This book follows my journey to find my Hakka identity. It explores our unique history of migration and shows how it shaped the Hakka character and cuisine. I traveled around the world and interviewed many Hakka who shared their stories and recipes in this book.

The Gourmand World Cookbook Awards recognized The Hakka Cookbook as Best Chinese Cuisine Cookbook in 2012.

You can order the book from your local bookstore. Or you can find it online at many outlets around the world such as Amazon and Kinokuniya. Click this link to find other sources for different areas. You can also buy the book directly from the publisher University of California Press.

This year a Taiwan publisher translated The Hakka Cookbook into Chinese. You can order the Chinese translation directly from SMC Books.