Hakka history, stories, and recipes

Recently I got a flurry of alerts from my blog to let me know The Hakka Cookbook had been mentioned in several posts online. Checking them I read a story introducing a new zine called “Eat Bitter” about a Hakka family and their food.

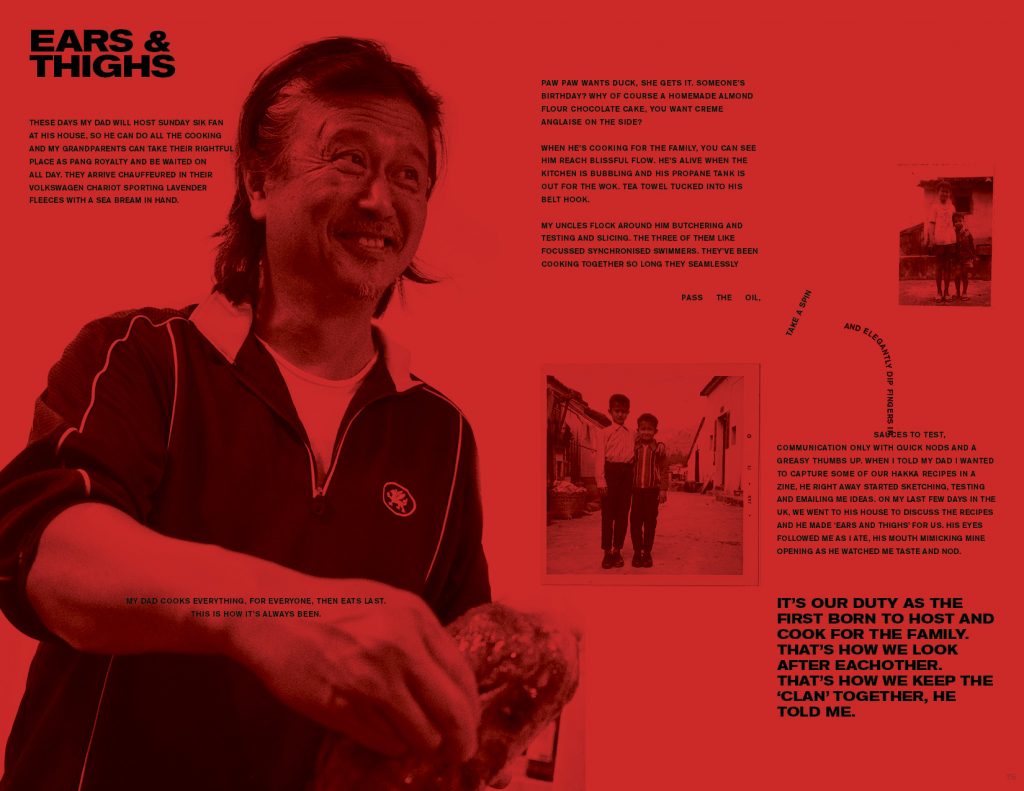

I was thrilled to learn that Lydia Pang, the creator of the new publication was a young Hakka woman. Pang, whose father is Hakka, grew up in Wales, a country without much cultural diversity. She had worked in more ethnically diverse London and New York and began to feel she didn’t know enough about her Chinese heritage. It was time to learn more. She decided to write about her family’s favorite foods and stories shared at the dinner table. The result, “Eat Bitter,” allowed her to explore her identity and preserve the culture and recipes of her Hakka family.

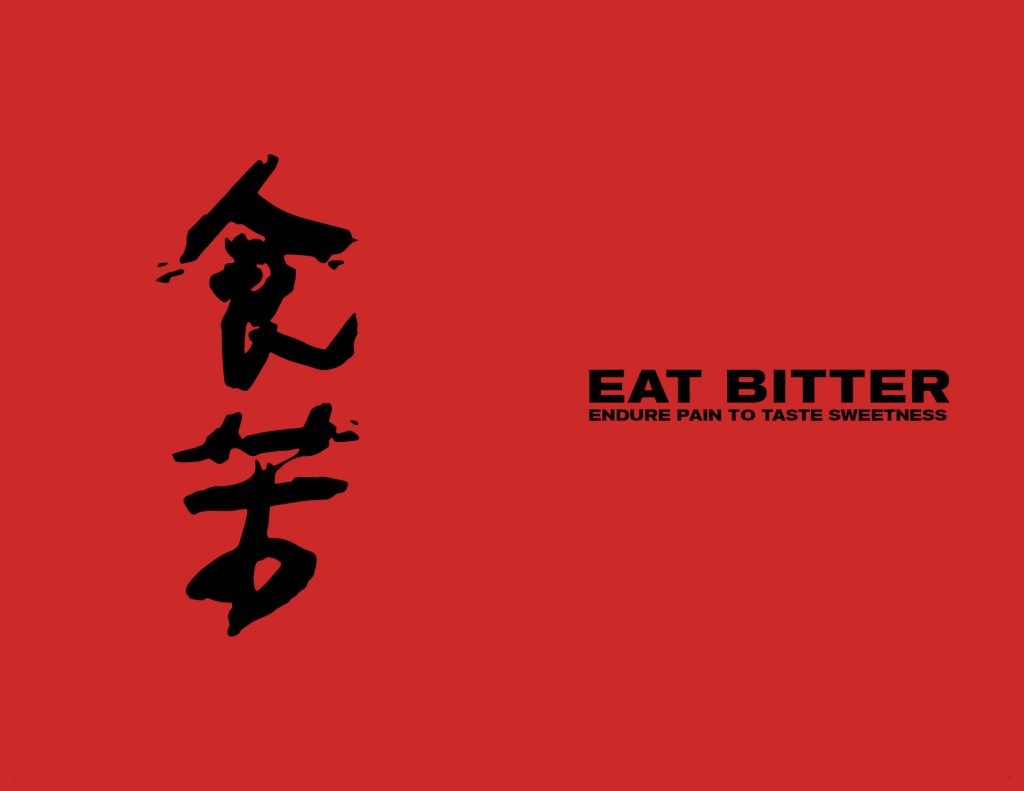

The title of her publication, “Eat Bitter,” reflects the Hakka history. The Hakka have long endured multiple migrations, hardship, and persecution. Called “guest people” because they often arrived to settled lands last, the Hakka got the meager leftovers. Through their hard work, they survived and flourished. Working through obstacles, whether in life or in the kitchen, makes the reward taste so much sweeter.

The zine’s bold design and creative layout vibrate on the red and black saturated pages (sample pages shown above). With help from her family, Pang records recipes such as Ears &Thighs (steamed chicken thighs and wood ear mushrooms), Fatty Pork (simmered pork belly with garlic and black beans), and Paw Paw’s Sponge (steamed sponge cake.) Photos and sketches reveal the cooking process.

To pre-order her magazine visit eatbitter.co Pang will donate a portion of the sales to Welcome to Chinatown, a grassroots organization that provides resources to hard-hit businesses in Manhattan’s Chinatown.