Who are the Hakka? Simply put, you might call them China’s nomads.

Who are the Hakka? Simply put, you might call them China’s nomads.

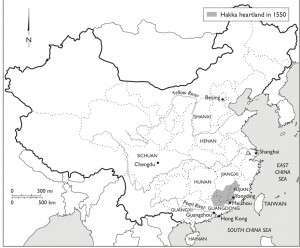

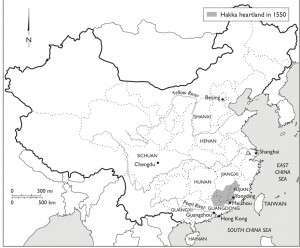

There are many theories about their origin. The story that most Hakka embrace is that around the fourth century, invaders forced the ancestors of the Hakka from their home in north-central China, once the cradle of the Han, or Chinese civilization. They fled south in a series of migrations. During a period of relative isolation from the tenth to almost the fourteenth century in southwestern Fujian province, they solidified their culture and language. By the time they reached the southern provinces, land was already settled so when the Hakka moved elsewhere they were considered the unwanted newcomers. The best, most fertile pieces of land were already taken. They were left with the scraps. They had no connected homeland and lived as dispersed minorities throughout Southern China.

The Hakka made the best of what they had and soon gained a reputation of being hard workers, pioneers who could survive almost anywhere. Other Chinese often looked down on the Hakka because they were migrants, unwanted newcomers, poor, independent, and clannish. In the twentieth century, the labeled them Hakka (Kejia in Mandarin) meaning guest people or family. Some Chinese called the women “big feet” because the Hakka did not follow the prevalent practice of foot-binding. It simply wasn’t practical. Women could not work in the fields with bound feet. Hakka women were feminists –independent, stubborn, strong, and hard-working.

Hakka women often wear a straw hat with a black veil attached around the edge of the brim.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Hakka proudly claimed their identity. Contact and conflict with other ethnic groups, especially during the Taiping Revolution (1851 to 1864) and the West River Hakka-Cantonese wars, fostered an ethnic group with a shared identity. After the wars, many Hakka left China to find a new life and escape the turbulence in their homeland. They emigrated to India, Southeast Asia, Taiwan, South America, Mauritius, North America, Tahiti, the West Indies, and many other destinations. Eventually they dispersed all over the world. Like dandelions, where ever they landed, they dug in, adapted, and flourished in their new homes.