Happy New Year! Khiung Hee Fat Choy! Wishing you prosperity, joy, peace, and good health!

Author Archives: lla

Chinese New Year Feast

Happy Chinese New Year! Celebrate the Lunar New Year with a Chinese New Year Feast. Greet everyone with “Happy New Year” (Xīnnián kuàilè in Mandarin 新年快乐) or “Wishing you happiness and prosperity!” (Khiung Hee Fat Choy in Hakka or Gong Hay Fat Choy in Cantonese 恭禧發財).

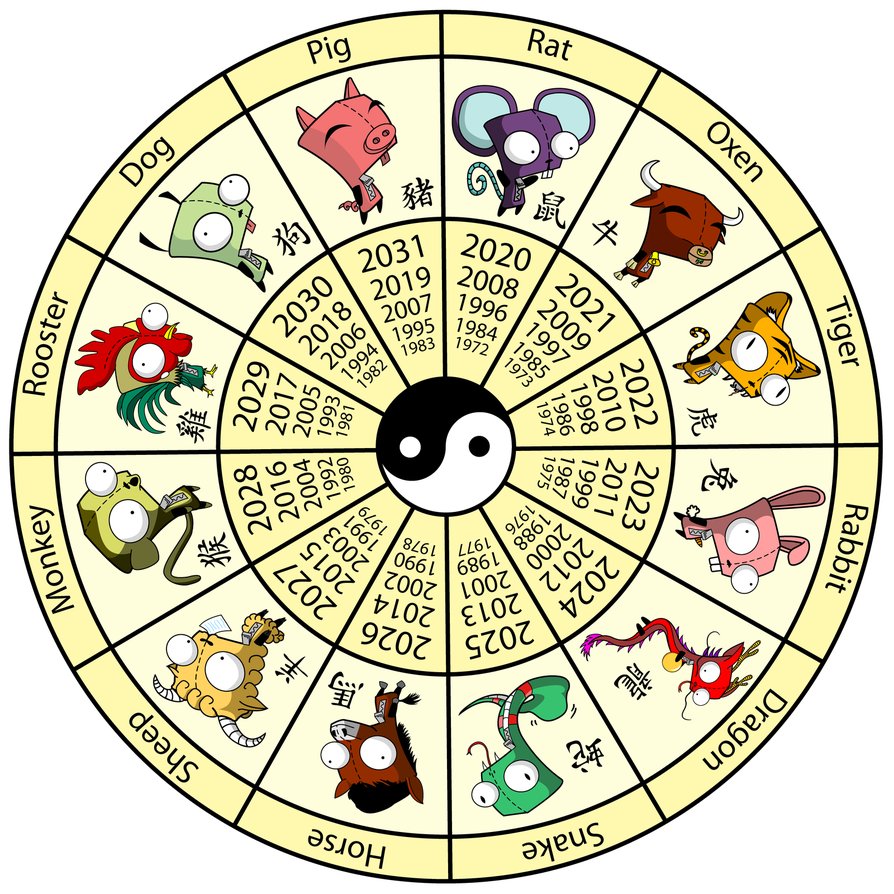

In 2026, February 17 marks the start of the Year of the Horse. On the Chinese horoscope, each year is dominated by an animal sign: Rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey rooster, dog, and pig. Each animal has special characteristics. If you were born in the year of 2014, 2002, 1990, 1978, 1966, 1954, and 1942, you are are a horse.

Some horoscopes describe people born in the year of the horse to be confident, intelligent, responsible, and stubborn. They like to be physically active and mentally challenged. Some forecasts for the horse show this may be a powerful year for growth and transformation. Balance your fire with calmness to make the most of this energy.

A family reunion feast starts the Chinese New Year celebration. Our family meal tends to be a cooperative effort with everyone sharing a dish. I’m scanning The Hakka Cookbook looking for recipes for our feast.

The table is traditionally filled with foods that send auspicious messages to attract wealth, luck, success, unity, longevity. Many foods eaten during the celebration have symbolic meanings. They may resemble or their words sounds like something that is auspicious.

Egg or spring rolls look like gold bars. Consider the Spicy Egg Rolls (page 184) or the Hakka Egg Roll page 170).

Open clams represent new opportunities. Perhaps I might cook Chile-spiced Clams with Basil and Cilantro (page 231).

Green vegetables suggest growth in business. Some options include Chinese Broccoli in Sweet Rice Wine (page 230), Stir-fried Chinese Lettuce and Wine Rice (page 50), Stir-fried Iceberg Lettuce and Garlic (page 27), Stir-Fried Snow Peas and Tofu (page 48), or Stir-fried Spinach and Peanuts (page 56).

Noodles symbolize long life. Choose from Garlic Noodles and Shrimp (page 193), Noodles with Mushroom Pork Sauce (page 104), Soy-glazed Pork and Mushroom Noodles (page 208), or Sweet Soy Chow Mein (page 178).

Round shaped foods represent unity. A Pork and Shrimp Ball Soup (page 213), Spinach and Fish Ball Soup (page 225), or Ginger Soup with Sweet Rice Balls (page 116) can bring the family together.

What will you eat for your Chinese New Year Feast? As long as you share food with family or friends, you start the year with good will and hope. Happy Year of the Horse! May it be full of joy, good health, prosperity, and peace!

Gift for someone with Hakka heritage

Looking for a holiday gift for someone with Hakka heritage? Consider The Hakka Cookbook, Chinese Soul Food from around the World. Named “Best Chinese Cuisine Cookbook” by the Gourmand World Cookbook Awards in 2013, its relevance endures.

It’s a perfect gift for one who wants to learn more about their Hakka history, identity, and cuisine. The book traces their struggles and migration across the world. Hakka from all over the world share their stories and recipes. I wrote the book especially for people like me, Hakka who didn’t know much about the history or people. Writing this book, helped me find my Hakka identity.

If you’re a Chinese food and history enthusiast, this book leads you to discover a relatively unknown group of Chinese known as Hakka (guest people.) Their unique history of a long migration shaped their strong survival characteristics, culture and cuisine. Even if you are not Hakka, you’ll find many history and food discoveries in the book. Art by my brother, Alan Lau, gracefully flows through the book.

Buy The Hakka Cookbook from the publisher, University of California Press or many places online. To buy a Chinese translation of the book visit the Taiwan publisher SMC Books.

Chinese comfort food, easy, effortless, and satisfying

Chinese comfort food, easy, effortless, and satisfying, make up the bulk of Hakka cuisine. In this recipe, braise chicken wings with just a few ingredients to produce a comforting dish that will please hungry diners. The secret ingredient is Chinese bean sauce. The dark salty bean sauce imbues the soft, silky chicken flesh and resulting sauce with intense savoriness. A generous measure of freshly ground pepper adds a slight spicy kick. After one taste, you may return to this Chinese comfort food dish over and over.

Secret Ingredient: Bean Sauce

Chinese bean sauce, aka known as Bean Sauce or Ground Bean Sauce is made with ground or whole fermented soybeans. The thick pasty sauce contributes a salty, pronounced fermented bean flavor, similar to soy sauce.

Look for the bean sauce in Asian supermarkets. If you can’t find it, shop for the more available hoisin sauce found in most supermarkets in the Asian sauce section. Omit the sugar when using the sweeter hoisin sauce.

Braised Chicken Wings in Bean Sauce

In a hot 14-inch wok or 5- to 6-quart over high heat pan, add 2 tablespoons salad oil. Add about 2 pounds chicken wing sections. Stir occasionally until wings are lightly browned. Stir in 2 tablespoons minced garlic. Add 2 cups water, 2 tablespoons bean sauce, 1 tablespoon each soy sauce and sugar, and 1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper. Cover and simmer over low heat, stirring occasionally, until the wings are tender when pierced, 35 to 45 minutes. Add a little more water as needed, if the liquid evaporates before the chicken is done.

With a slotted spoon, transfer the wings to a serving dish. Skim fat off pan juices, and if the sauce tastes watery, boil, uncovered, to concentrate flavor and reduce the sauce to about 1 cup. Pour over the wings. Garnish with thinly sliced green onions or cilantro.

For more recipe details, see page 203 of The Hakka Cookbook. Serve with rice and stir-fried greens. Thanks to Fah Liong, my Hakka friend who taught me this easy and satisfying dish. Enjoy!

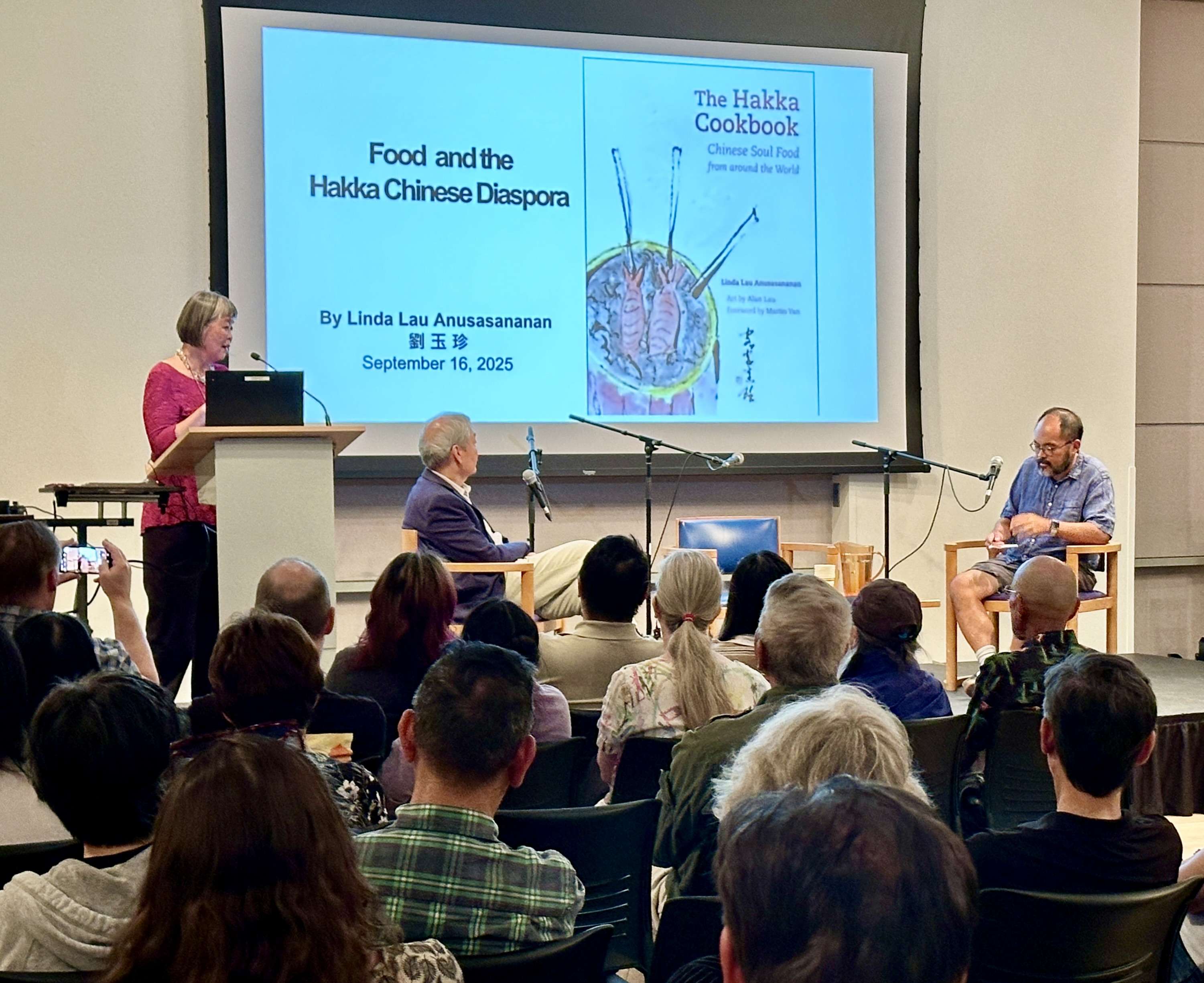

Food and the Chinese Diaspora

The event, “Food and the Chinese Diaspora” began over a year ago when my friend, Judy Lam Maxwell proposed that Cheuk Kwan, author of Have You Eaten Yet? and I, author of The Hakka Cookbook, talk about Chinese food around the world at a public event in Vancouver, BC. This dream finally took place at the Vancouver Central Public Library a few days ago. Kevin Chong, author and professor moderated our conversation.

I couldn’t believe that 186 people registered for this free event. Even if not everyone showed up, this promised to be a good crowd. After a short video from Cheuk and a slide show from me, Kevin guided our conversation about food and the Chinese diaspora. We talked about eating in Peru, strong Hakka women, authentic food, Hakka-Indian restaurants, recording recipes, pork belly, and much more. Since Cheuk and I both traveled the world to eat Chinese food to research our books, it was a fun and spirited conversation. View the discussion here.

The audience was the BEST–attentive, interested, and responsive. Many Hakka asked questions or made comments. I’ve always felt a warm welcome from my Canadian audiences. Thank you Vancouver!

Many THANKS to those who made it happen! If you missed the event, view Food and the Chinese Diaspora here.

- Judy Lam Maxwell for conceiving and organizing this event, and bringing it to the world.

- Candice Tanaka from Vancouver Public Library for setting up the event at the Central Library.

- Cheuk Kwan, author of Have You Eaten Yet?, for sharing his experiences, support, and wisdom.

- Kevin Chong, author of the Double Life of Benson Yu, for keeping the conversation interesting.

- Nooroogi Books who provided books for sale.

- Larry Chin of Chinatown Wonders who provided The Hakka Cookbook for sale.

Food and the Chinese Diaspora

Join Cheuk Kwan, author of Have You Eaten Yet? and me, author of The Hakka Cookbook, Chinese Soul Food from around the World as we discuss “Food and the Chinese Diaspora.” In our books, we both interviewed transplanted Chinese around the world on what they ate and cooked. We asked what motivated them to move? Kevin Chong, author of The Double Life of Benson Yu will guide the conversation. Judy Lam Maxwell, culinary-heritage tourism entrepreneur will introduce the group.

To register for this free event at the Vancouver Public Central Library, click this link. Register soon, only a few seats left.

Food and the Chinese Diaspora

- Tuesday, September 16, 6:30 to 8 pm

- Central Library, 350 West Georgia Street, Vancouver BC, V6B6B11

- [email protected] or (604) 331-3603

- Register here

In partnership with Asian Canadian Writers Workshop.

Books will be available for purchase from Nooroongji Books.

My Hakka Savior

With the publication of the Chinese translation of The Hakka Cookbook in Taiwan, my audience grew. Recently the Taipei Hakka Cultural Quarterly, published by the Hakka Affairs Council of Taipei City Government asked me to write a personal story about family, Hakka cuisine, and memories. My story about my grandmother, ”My Hakka Savior” was just published in their online magazine.

I wrote about how my Hakka grandmother helped my family adjust and thrive in a small conservative town where we were the first and only Chinese. Her Hakka spirit with a strong work ethic, ability to adjust, and business savvy, guided our family to a path of survival in a difficult and stressful new environment.

I wrote the article in English and the magazine translated it into Chinese. Their design team cleverly worked visual elements of my story into the layout. If you can read Chinese, and would like to read the complete magazine, click this link.

To read a pdf that includes Chinese and English, download the following file or click this link.

What is Hakka Food?

What is Hakka food? I grew up in California eating Chinese food at home with occasional nights of tacos, spaghetti, and chicken pot pies. Most of our meals centered around a bowl of rice. I really didn’t give much thought if the food was Hakka or Chinese, to me it was just comfort food.

It wasn’t until I started researching this book that I tried to define Hakka food. I asked every Hakka I met and got many answers: satisfying, fatty, robust flavors, rustic food of the working man. Preserved vegetables and meats play a prominent part in their diet. Soy sauce, rice wine and their by-products, fermented bean curd, and fermented bean sauces season the foods.

But as I ate Hakka dishes around the world, the definition seemed to encompass a much wider range of foods. Many of the Hakka classics fit the previous definition, but what the Hakka eat today maintains traditional flavors but also adapts to their new adopted homes and a different lifestyle than their ancestors. Fresher ingredients, more seafood, and new seasonings broaden the diet. Innovative Hakka cooks add variety, lighten dishes, and create new recipes.

Some Cantonese might try some of the recipes in this cookbook and say it tastes like what they ate at home. It’s not a coincidence. Some call Hakka food the country cousin of Cantonese cuisine. It makes sense. Both groups lived side-by-side, although not amicably, in southern China for centuries. Abroad, they were often forced to live together. So many dishes bear a similarity. Even at Cantonese restaurants, often a few Hakka dishes appear on the menu.

Compared to Cantonese dishes, I find Hakka food tastes more satisfying, with stronger flavors. Because many Hakka lived inland, seafood was not readily available. Pork stews and braised chicken, often dark with soy sauce, were common. Yet many dishes, especially fresh vegetables were simply cooked, letting natural flavors emerge. Preserved vegetables, meats, and seasonings also played a prominent role in their diet because these foods lasted a long time, an asset for those who migrated often and whose access to fresh ingredients were sometimes limited. Salt and dehydration extended their shelf life and attributed a salty flavor to some of the finished dishes.

For me, Hakka food is Chinese soul food. It comforts my soul and satisfies my stomach.

Fu Pei-Mei, author and Taiwan television culinary teacher

I recently read Chop Fry Watch Learn, Fu Pei-Mei and The Making of Modern Chinese Food by Michelle T. King. Her book tells the story of Fu Pei-Mei, author and pioneering Taiwan television personality who made Chinese cooking achievable for home cooks.

I read King’s book because I own a copy of Pei Mei’s Chinese Cookbook. I bought Pei Mei’s book in San Francisco Chinatown when I first started my career as a food writer in the early 1970’s. Compared to the glossy cookbooks of today, this book looks rather plain and simple. Yet it fulfilled a need. This ground-breaking book made Chinese cooking accessible to busy home cooks in a changing society.

In 1949 Fu immigrated to Taiwan from mainland China. She married two years later. Like many young post-war housewives, she found herself confronted with the realities of cooking daily meals for her family. Frustrated with her food failures, she educated herself through lessons with chefs and more experienced home cooks. As she gained a reputation for her cooking, she shared her knowledge with other housewives. In 1962, Taiwan Television asked her teach on the screen. Her first show led to a career as a television culinary instructor that spanned four decades. Her recipes modernized Chinese cooking and spread throughout Taiwan and the world, even to King’s and my kitchen in America.

I was pleasantly surprised to find The Hakka Cookbook listed in Chop Fry Watch Learn. As I finished the book, I saw my name in Suggested Readings, under Chinese Cookbooks on page 286. Under the heading, the author writes “I like these cookbooks because they combine recipes with personal stories.” Thank you Michelle T. King for the shout out. If you’re interested in Fu Pei-Mei and how she influenced modern Chinese cuisine, read Chop Fry Watch Learn.

Taste the Hakka soul in this pork and mustard green stew

Taste traditional Hakka flavors in this easy pork stew. This dish pairs two Hakka staple ingredients, salted mustard greens and pork. They simmer together with a generous dose of garlic and rice wine. Dark, sweet soy sauce gives it a deep inky hue and salty-sweet-sour flavor. The result tastes distinctively Hakka.

Fah Liong, my Hakka mentor, contributed this recipe to the The Hakka Cookbook. Her Indonesian roots show up in her use of kecap manis, an Indonesian sweet soy sauce. The syrupy soy sauce infuses the stew with a dark, glossy, finish and a salty, sweet, taste. The salted mustard greens, popular in Hakka dishes, balance the richness of the pork and the sweetness of the soy sauce. Serve the soy-braised pork with mounds of hot rice.

Soy-Simmered Pork and Salted Mustard Greens

For a more detailed recipe, see page 222 in The Hakka Cookbook. The dish can be made a day ahead made; cool, cover, and chill. Reheat, covered, over low heat, adding a little extra water, as needed.

3 cups salted mustard greens (about 1 1/4 lb.), rinsed and cut in 1 1/2-inch squares

¼ cup vegetable oil

⅓ cup minced garlic

2 pounds boneless pork butt, cut in 1 1/2-inch chunks

2 cups Chinese rice wine (shaoxing) or dry sherry

3 tablespoons kecap manis (Indonesian sweet soy sauce) OR mix 2 tablespoons each dark soy sauce (see notes, following) and packed brown sugar

2 tablespoons sugar, or to taste

2 tablespoons dark soy sauce (or 4 teaspoons light or regular soy sauce plus 2 teaspoons molasses)

Salt

- Soak the mustard greens in water at least 1 hour or up to 4 hours, changing water occasionally. Drain and squeeze excess water out of the mustard greens.

- Set a 14-inch wok or 5- to 6-quart pan over high heat. When pan is hot, add the oil and garlic. Stir-fry until garlic is lightly browned, about 15 seconds. Add the pork and cook, stirring occasionally, until meat is lightly browned, 5 to 8 minutes. Add the wine, mustard greens, kecap manis, sugar, and dark soy sauce.

- Bring the pork mixture to a boil. Reduce the heat, cover and simmer, stirring occasionally, until the pork is tender when pierced, 1 ½ to 2 hours. If liquid evaporates before the meat is tender, add a little water as needed, and continue simmering. With a slotted spoon lift out pork and mustard greens and transfer to a serving dish. Skim off the fat from pan juices and discard. Taste juices and if too watery, boil, uncovered, over high heat until juices are reduced to about 1 cup. Taste and add salt and more sugar, if needed. Pour over pork. Makes 6 to 8 main-dish servings.

Notes: For a quick substitute for dark soy sauce (aka black soy sauce, double black soy sauce, mushroom soy sauce) use 2 parts light or regular soy sauce plus 1 part molasses